Untapped Potential for Child Welfare Administrative Data

Author: Dana Hollinshead, PhD, MPA

Although a lot of data are captured through child welfare management information systems, there is much we still need to learn about the experiences of children and families involved in child protective services, and especially why some fare better than others. This is especially true with respect to dynamics that may influence caseworkers’ decisions, actions, and case outcomes. For example, are there certain caseworkers or service providers who are more effective in engaging families? Is there something about the type or dosage of services that makes a difference? Which workers or supervisory units are more likely to place a child in out-of-home care? Is caseworker turnover pivotal in shaping the trajectory of a case? What policies and practices may explain differences in outcomes within and between states and over time? While child welfare administrative data systems have become more robust in the decades since the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis System (AFCARS) and National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) were designed, we still lack critical insights into caseworker and family dynamics, the impact of policies, and other factors affecting outcomes. The QIC-WD has worked with a variety of public child welfare agencies and identified untapped opportunities to better utilize (or expand) existing data systems. This QIC-Take highlights some concepts to consider during system redesigns and/or implementation of expanded, interoperable cross-system data exchanges focused on case management, such as the Comprehensive Child Welfare Information System (CCWIS).

What We’re Seeing

NCANDS and AFCARS data were designed and are largely for accountability purposes. Therefore, they were not created to answer longitudinal research questions and inquiries into factors affecting outcomes. It is challenging to pair NCANDS and AFCARS data to produce a longitudinal view of all events associated with a child or family (comprehensive linkage is only beginning; see Drake et al., 2021). To examine case outcomes, we need a more complete picture of case dynamics (e.g., caregiver and household attributes, not just perpetrators’, and how they change over time), history (e.g., all placements not just the first, second, and last or indicators of runaway chronicity), and/or case acuity (e.g., measures of severity, workload-related intensity, and/or worker-level safety or risk). As frontline staff will attest, there is much more complexity in the dynamics underlying case outcomes than current data systems capture. Our understanding of why outcomes were or were not achieved must take these dynamics into account, but current data systems at both the state and national level make this challenging.

Child welfare agencies often struggle with producing comprehensive data on service provision, dosage, engagement, completion, and quality. Typically, only services that are paid for by the agency are tracked and information about service providers who engage with children and families is generally lacking. Without a holistic picture (of service referrals, usage, engagement, and completion), fundamental insights into the formal and informal supports offered to families are absent. The opportunity to specify which resources and individual providers (e.g., caseworkers or other service providers) are more effective in supporting children and families in reaching their goals is also missing.

Child welfare agencies often struggle with producing comprehensive data on service provision, dosage, engagement, completion, and quality. Typically, only services that are paid for by the agency are tracked and information about service providers who engage with children and families is generally lacking. Without a holistic picture (of service referrals, usage, engagement, and completion), fundamental insights into the formal and informal supports offered to families are absent. The opportunity to specify which resources and individual providers (e.g., caseworkers or other service providers) are more effective in supporting children and families in reaching their goals is also missing.

Agencies and tribes cannot answer some workforce questions because data are not captured in CCWIS, SACWIS or non-SACWIS case management information systems. For example, administrative data may show start and stop dates for multiple workers on a case, but not indicate the role each staff person on a case. As a result, it is often difficult to determine which worker had responsibility for decisions, or if team decision-making with a supervisor or other staff were used. Yet we know from research that the identity of a caseworker can have a material effect on decisions that set the trajectory of a case, whether in the form of consistently elevated risk assessment scores (Graham et al., 2015) or decisions to place children in out-of-home care (Graham et al., 2015; Hollinshead et al., 2021).

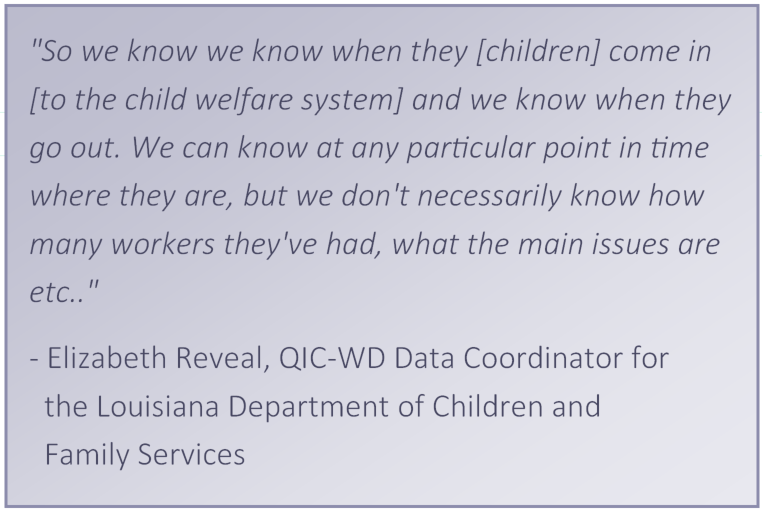

We also lack information about the role of caseworker turnover, despite indications that turnover may adversely impact child and family engagement, case progress, and closure. For example, data reflecting counts of the number of workers associated with a case and the degree to which children and families have experienced discontinuities are not routinely captured. This is an on-going challenge despite the field’s longstanding concerns about the issue. Moreover, we do not know to what extent some turnover is a good thing (i.e., functional turnover); what if the worker who left was someone unable to connect with children and families in crisis and thus ill-suited to the job? Better turnover data and the tools to connect turnover to case outcomes are needed.

The structure, focus, and functioning of work units is also rarely indicated in existing data sets. For example, we don’t always know if a worker wears many hats (i.e., everything from investigations to adoptions), specializes in one area, or follows a case from start to finish. It is often difficult to quantify caseloads when responsibilities are shared across multiple staff, cases shift from one stage to another (e.g., in-home services to out-of-home placements), and other daily variations occur (e.g., closures and new assignments). The field also lacks fundamental insights into whether differences in the structure and function of work units (e.g., CPS only, foster care only vs. multi-stage units) may yield more or less stressful work environments for staff and/or have a material impact on dynamics of child and family engagement and outcomes.

The structure, focus, and functioning of work units is also rarely indicated in existing data sets. For example, we don’t always know if a worker wears many hats (i.e., everything from investigations to adoptions), specializes in one area, or follows a case from start to finish. It is often difficult to quantify caseloads when responsibilities are shared across multiple staff, cases shift from one stage to another (e.g., in-home services to out-of-home placements), and other daily variations occur (e.g., closures and new assignments). The field also lacks fundamental insights into whether differences in the structure and function of work units (e.g., CPS only, foster care only vs. multi-stage units) may yield more or less stressful work environments for staff and/or have a material impact on dynamics of child and family engagement and outcomes.

Context also matters. While policy changes are typically not frequent, when they happen, they can impact the data being analyzed and outcomes being assessed. Jurisdictions examining trends over time need to understand such dynamics and take them into account in continuous quality improvement (CQI) efforts. For example, we know that jurisdictions using differential response systems have lower re-report (Fluke et al., 2018), out-of-home placement (Loman & Siegel, 2015, Marshall et al., 2010), and recurrence rates (Hollinshead, 2012). We also know that a higher level of evidence required to substantiate a child maltreatment report is associated with lower substantiation rates (Flango, 1991; Fluke et al., 2001). Still, there is often inadequate attention given to the how the implementation or suspension of policies affects child welfare work experience, whether related to practice (e.g., formally investigating all new reports on open cases), human resources (HR) dynamics (e.g., across the board raises, permission to telework), or engagement of families (e.g., use of differential response). To date, there are few formal efforts to track policies and changes over time within states or across the country and those that do exist are limited in scope (Mathematica, 2021).

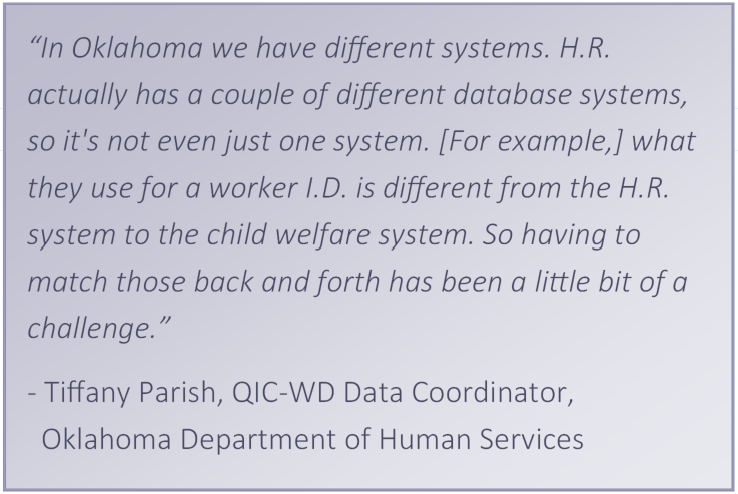

Lastly, agencies across the U.S. collect, but do not use, a lot of their data on the workforce to better understand how children and families served. While some jurisdictions have access to workforce analytic support resources, many do not. Furthermore, some jurisdictions have antiquated child welfare and/or HR systems that are only accessible through a single person. With the advent of Families’ First (FFPSA), the need for rigorous implementation research as well as actionable inquiries has never been more urgent. Thus, a critical need in our field is a more focused and robust effort to foster technical and workforce capacity-building on this front.

Lastly, agencies across the U.S. collect, but do not use, a lot of their data on the workforce to better understand how children and families served. While some jurisdictions have access to workforce analytic support resources, many do not. Furthermore, some jurisdictions have antiquated child welfare and/or HR systems that are only accessible through a single person. With the advent of Families’ First (FFPSA), the need for rigorous implementation research as well as actionable inquiries has never been more urgent. Thus, a critical need in our field is a more focused and robust effort to foster technical and workforce capacity-building on this front.

Looking Ahead

Public child welfare systems looking to understand why some work units (i.e., caseworkers, offices, or regions) vary with respect to aggregate case outcomes currently have few resources to conduct these inquiries and little information about what is happening in other jurisdictions. These concerns represent untapped opportunities to capture and analyze data that may yield better information that can be leveraged to improve outcomes for children and families. Efforts to enhance agencies’ capacity to use the data they collect do exist. In 2020, the QIC-WD held an analytics institute focused on training eight sites to enhance their utilization of human resources and child welfare data; materials and guides available for public use can be found here. Moreover, with the redesign of AFCARs, we hope we will see a more comprehensive view of placement trajectories. Still, CCWIS redesign initiatives offer opportunities for jurisdictions to think boldly about how to capture and design these systems to truly understand why some children and families have better child welfare outcomes. These include identifying and exploring assumptions about why outcomes vary as they do. They also provide an opportunity to collect more robust case, services, worker, unit, agency, and policy or practice data that capture changes over time. By developing and testing the theories of change underlying these assumptions, and using the data to support CQI efforts, agencies can be better positioned to fulfill the mission to improve child, family and community well-being.